The Lighthouse Contract Protocols 2026

Balanced, court-savvy clauses: A field guide to pragmatic, cooperative business dealings.

With extensive case citations, pro tips, and other notes.

For students and business people: Use this book to help understand how companies work together to get business done quickly and smoothly.

For lawyers: Break free of hamster-wheel negotiation — and get deals done faster — by adopting selected Lighthouse protocols in a binding term sheet or LOI, to reduce costs and help guard against gamesmanship. (Especially useful in smaller matters.)

By DC Toedt (about), professor of practice, University of Houston Law Center; member of the State Bars of Texas (active) and California (inactive). Working draft — saved 2026-01-31T17:51Z. Copyright © 2024-26 D. C. Toedt III; see 1.1 below for Creative Commons authorization.

• Example 1 – an instant NDA by email: Party A: "Let's use the LCP26 NDA Protocol — agreed?" Party B: "Yes."

• Example 2 – a quick NDA negotiation by email: Discloser: "Let's use the LCP26 NDA Protocol and and Business Associate Agreement Protocol — does that work?" Recipient: "Could we add [a specified Recipient-playbook option]?" Discloser: "Done!"

• Bonus: Many Lighthouse protocols are written in checklist-style format as an aid to legal review of conventional contract drafts.

IMPORTANT: Don't rely on this book as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed attorney. It's provided AS IS, WITH ALL FAULTS, with no warranties express or implied. Oh, and: I'm not your lawyer unless we've entered into a written engagement agreement.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

Contents:

1.1. Creative Commons distribution license

This book may be reproduced and/or distributed under the Creative Commons BY-SA license 4.0: Attribution required; share any revisions in the same way. See the CC license for details.

1.2. Target readerships

This book aims to serve readers in several categories:

- If you're a law student:

- You likely want to get a sense for how business deals are actually done in the real world — especially deals for smaller clients, whom you might represent sooner than later in your legal career.

- You also want to know how, as a new lawyer, you can draft contract language that will pass muster with your supervising attorney and not someday result in a [hacked]-off client and/or malpractice carrier.

- You might well wonder whether artificial-intelligence will ruin your chances of getting decent training after graduation because AIs are taking over more of the routine work of law-firm junior associates in drafting contracts and reviewing other parties' drafts.

- If you're a lawyer, you probably value curated clauses that you can use as issue checklists and language sources.

- If you're a lawyer's client, chances are that sometimes you have to read, understand, and actually carry out contracts.

- In a contract dispute, all concerned will want to quickly and accurately grasp what the parties agreed to, including:

- the parties' managers and even senior executives;

- their litigation counsel;

- judges and their law clerks, reading the contract "cold"; and

- jurors (albeit rarely).

In writing the Lighthouse protocols and elsewhere in this book, I've tried to keep in mind:

- What tasks will these different readers be taking on?

- For each of those tasks: How can this book help the reader get the work done faster — better — cheaper? (Business folk might recognize this as perhaps an offshoot of one aspect of design thinking, reflected in the late professor Clayton Christiansen's question: What job is your customer buying your product for?)

1.3. Client goals for contracts

Most business people would agree that they usually care about:

- getting contracts signed as quickly as possible, because the people involved have lots else to do;

- guarding against unscrupulous behavior by The Other Side;

- planning for a reasonable set of what-if contingencies; and

- building resilient commercial relationships.

And when possible, businesses prefer dealing with counterparties —

- who're agreeable to work with; and

- who, when challenges arise, take reasonable positions and seek amicable solutions.

For example, customers want to do business with vendors who have proved their reliability as suppliers of goods and services — especially when things get tough, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic and the attendant supply-chain disruptions. See, e.g., Xiwen Bai, Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, et al., The Causal Effects of Global Supply Chain Disruptions on Macroeconomic Outcomes: Evidence and Theory, Nat'l Bur. of Econ. Research Working Paper 32098 (NBER.org 2024); Tacy Foster, Supply chain risk pulse 2025: Tariffs reshuffle global trade priorities (McKinsey.com 2025).

And vendors prefer dealing with customers who pay on time and who provide repeat business and favorable referrals.

In that vein: The global not-for-profit trade association World Commerce & Contracting* has as one of its stated purposes "… to transform contracts and the contracting process, such that they become instruments of fair dealing, that they themselves, and the process surrounding them, promote trust, [and] generate economic benefit …." * WorldCC (formerly the International Association for Contract and Commercial Management) has some 80,000 members representing more than 20,000 companies across 180 countries.

Unfortunately, some lawyers forget that in day-to-day contract negotiations, what clients want is not to prevail on as many points as possible, but instead:

- to get an "OK" contract signed as quickly as possible, so they can get on with the rest of their to-do list — this is true whether you're representing a vendor or a customer;

- to try to minimize the legal spend; and

- to have a good experience with the other company and its people — building mutual trust as reliable business partners who could work together again and who might have each other's backs in a crunch. (See also the discussion of trust at 31.39.)

Especially for business clients, the perfect is the enemy of the good. That can sometimes be jarring to lawyers, because we're professionally socialized to focus above all on our ethical duty of "zealous advocacy" for the client's position. We sometimes misinterpreted that duty as attempting to put the client in the absolute best possible litigation position, for every conceivable situation — no matter how much the attempt might delay getting the deal done and possibly leave a bad taste in everyone's mouth.

(On that last point, see possibly the greatest lawyer cartoon of all time.)

Students: The W.I.D.A.C. Rule applies here: When in doubt, ask the client.

The Lighthouse protocols aim to support these goals

1.4. About the author

I’m DC Toedt, a professor of practice at the University of Houston Law Center and a practicing attorney in Houston. I’m licensed in Texas (active), California (inactive), and the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

(People often ask: My full name is Dell Charles Toedt III; my German-origin last name is pronouced "Tate," in the same way as former House speaker John Boehner, pronounced "BAY-ner." Because of my Roman numeral III, my family has always called me "DC.")

As a lawyer, I "came up" at Arnold, White & Durkee, a 150-lawyer intellectual property litigation firm, where I was an associate and then a partner, and was eventually elected to the management committee. We were one of the largest such firms in the United States, with offices in six different cities with significant tech industries.

I left AW&D during the dot-com boom to become vice president and general counsel of BindView Corporation, a publicly-traded, 500-employee software company, with offices in six countries. As outside counsel, I’d helped the founders start the company and joined them full-time not long after the company went public. I served there — negotiating probably hundreds of contracts — until our "exit," when we were acquired by Symantec Corporation, the world leader in our field.

Since leaving BindView I've maintained a limited solo practice helping tech companies, both established and startups. In addition, since 2010 I've taught a contract-drafting course at UH — for which this book serves as the main reading — and since 2021, an annual IP-introduction course for Rice University MBA students.

Among other past publications, I was the lead author and editor of The Law and Business of Computer Software, a one-volume treatise.

I’ve been active in bar-association work throughout my career; I also work pro bono with certain nonprofit organizations.

Both my undergraduate degree (in math, with high honors, including extensive science coursework) and law degree (law review) are both from the University of Texas at Austin.

Between college and law school, I served five years in the U.S. Navy as a nuclear-reactor engineering officer, and as one of the officers of the deck underway, aboard the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise, with two extended "Westpac" deployments, paying back a full-ride Navy ROTC scholarship at UT Austin.

Any views I might express here are my own, of course, and not necessarily those of clients, former employers, etc., etc.

2. Business- and drafting philosophy

Contents:

- 2.1. Freaky Friday terms: Breaking free of negotiation kabuki

- 2.2. Communication

- 2.3. Form follows function (or should, at least)

- 2.4. The Great Rule: Serve the Reader!

- 2.5. The Spaghetti Rule: Short, single-subject paragraphs

- 2.6. The BLUF Rule: Bottom Line Up Front!

- 2.7. Looking ahead to the Age of AI

2.1. Freaky Friday terms: Breaking free of negotiation kabuki

Contents:

- 2.1.1. Clients get impatient with the typical lawyer approach

- 2.1.2. Treat the contract draft like a (separate) product offering

- 2.1.3. 'User reviews' of our contract … from customers' lawyers

- 2.1.4. A sales force standing ovation

- 2.1.5. But was it a 'safe' contract?

- 2.1.6. The key: Freaky-Friday terms

- 2.1.7. Freaky-Friday contract terms allow for role-swapping

- 2.1.8. Counterexample: A Trump building lease backfires

- 2.1.9. Freaky-Friday terms can be safer for both the parties and the drafters

- 2.1.10. Caution: A supposedly role-swappable draft can be biased

2.1.1. Clients get impatient with the typical lawyer approach

As a young lawyer in a big law firm, I somehow picked up the notion that, when drafting any contract:

- you load up your draft with a wish list of things that your clients would love to get — or that could someday give your client leverage over the other side — with an eye to planning for every worst-case scenario you can think of;

- you send your draft to the other side — which sends it back to you, marked up with their wish list;

- in all likelihood, you and the other party go back and forth, exchanging multiple drafts and possibly doing one or more conference calls;

- finally, you compromise somewhere.

For both parties, the overall mindset there was: If you lead off by asking for the moon, in the end you'll get more of what you wanted. This can be seen in advice from the late negotiation guru Chester L. Karrass, whose unsmiling visage could be seen in airline-magazines ads for his training courses. Dr. Karrass's namesake organization still urges parties to anchor their negotiations by aiming high with "a [b]old [f]irst [o]ffer" and then bargaining down from there.

(And of course in much the same vein is Donald Trump's best-selling 1987 book The Art of the Deal.)

Where everyday contracts were concerned, I was quickly "counseled" about a different perspective almost as soon as I joined BindView Corporation as the company's first in-house lawyer. BindView had been a long-time client (I'd helped the founder to start the company). Suddenly I was handling all of the routine negotiations with customers about our standard contract form.

That turned out to be a big time drain. And not just for me: For our sales people, who'd commonly sit in on some of my legal-negotiation calls with their customers to keep an eye on things. Whenever we negotiated our standard contract with a customer, we usually ended up conceding the same points, over and over — like hamsters running in a wheel. I soon wondered whether this was really necessary.

And our sales people had better things to do, too: Especially as the end-of-quarter cutoff date drew near, they'd have much preferred to be working on closing more deals with other customers. (If I had a nickel for every time a sales person or senior exec had asked me: Can't we just use a short contract that's reasonable for both sides? …)

2.1.2. Treat the contract draft like a (separate) product offering

Every time you send a draft contract to another party, it's as though you're trying to 'sell' the other party on a product — i.e., the contract itself — which the other party might find itself having to use years later. That realization paid off for my former company, BindView: We wanted to break out of the negotiation hamster wheel as much as possible when negotiating customer contracts. Our C-suite management agreed to try something different:

- Over several months, whenever we negotiated workable changes in our contract, we made similar changes to our standard contract as well (with approval from the business execs, of course).

- This resulted in our contract being a 'product' in its own right — one that, out of the box, gave customers pretty much what they wanted. (And it did so in ways that we knew that we could support operationally (and, in my judgment, didn't significantly increase the company's legal exposure.)

Moreover: I made it clear to our sales people that I wouldn't even look at a customer's contract form until the sales team got me a five-minute phone call with the customer's contract people. I told the sales people that it was my job to try to sell the customer on our contract. (That alone helped speed up our sales cycle: Sometimes we ended up having to use the customer's contract after all. But that first call with the contract people gave both sides a sense of who they were dealing with; this helped each side assess what terms could be agreed to.)

2.1.3. 'User reviews' of our contract … from customers' lawyers

A side benefit of BindView's new approach was that our (re)balanced contract form helped sell our products: Customers' lawyers began to say how much they liked our contract. This helped to validate those customers' decision to do business with us.

I started making notes of the lawyers’ favorable comments. I quoted some of the comments (anonymously) on a cover page of our contract form. Here are just a few of those comments, which I posted online some years ago; all are from conference calls:

- From an in-house attorney for a multinational health care company: "I told our business people that if your software is as good as your contract, we’re getting a great product." (!)

- From an in-house lawyer at a U.S. hospital chain: "I giggled when I saw the 'movie reviews' on your cover sheet. I’d never seen that before: customers saying this was the greatest contract they’d ever seen. But the comments turned out to be true."

- From a contract specialist at a national wireless-service provider: "I told my boss I want to give your contract to all of our software vendors and tell them it’s our standard contract, but I know we can’t do that." (!)

- From an in-house attorney at a global media company: "This is a great contract. Most contracts might as well be written in Greek, but our business guys thought this one was very readable."

2.1.4. A sales force standing ovation

A few months after BindView had begun this transition to a customer-friendly contract form, we acquired a smaller software company by the name of Entevo. After we closed the acquisition, our sales organization brought Entevo's sales people to Houston for onboarding, including training in how to sell our software. During a break at one of those sales-training sessions, our VP of worldwide sales, David Pulaski (who said I could use his name in telling this story) stuck his head in my office.

David said he'd told our new sales reps that, unlike at Entevo, at BindView we did most of our deals on just a one-page sales quotation and our clickwrap license agreement, which was customer-friendly just like our negotiable contract form. David said that our new sales reps had given him a standing ovation.

Why the standing-O? Because our new sales reps remembered how at Entevo, they'd had to use a detailed contract form that had lots of vendor-protective legalese. Not surprisingly, Entevo's customers had often insisted on negotiating the contract's legal terms and conditions, which the CFO handled. (Entevo didn't have an in-house lawyer.) That had sometimes slowed up Entevo's getting deals signed, causing some grumbling among Entevo's sales people.

So when David told the our new reps about BindView's approach, the reps instantly recognized that their work had just gotten easier: For most BindView sales oppotunities, our new reps could just quote a price; reference our clear, fair set of terms; and get the deal signed — helping the reps to make their quotas and earn commissions and club trips for themselves .

David's story has stuck with me, helping inspire the framing of this book: Fair, readable agreements help to cut deal friction — especially for smaller-dollar transactions.

2.1.5. But was it a 'safe' contract?

You might wonder whether BindView ever experienced legal- or business problems from having a balanced, customer-friendly contract form. I’ll note only that:

- With the CEO’s permission, I talked about our contract philosophy in continuing-legal-education (a.k.a. CLE) seminars, and even included a copy of our standard form in written seminar materials;

- We basically-never had any kind of contract-related problem with a customer when we'd used our contract form; and

- In due course we had a successful 'exit': Having navigated through the software industry's 'nuclear winter' after the dot-com crash, we were approched and acquired by Symantec Corporation, one of the world’s largest software companies and the global leader in our field.

2.1.6. The key: Freaky-Friday terms

.png)

A useful way to write sellable contracts is to put yourself in the shoes of The Other Side. Let's (provisionally) assume that a contract clause is serviceably balanced if it provides role-swappable terms: We could define that expression as terms that A wouldn't be averse to agreeing to if A were to find itself in B's shoes (or vice versa, obviously), in the manner of the Freaky Friday movies.

Or for readers of a certain age: where A and B are like the characters played by SNL alumni Dan Ackroyd and Eddie Murphy in the 1983 movie Trading Places (which coincidentally also featured Jamie Lee Curtis, who starred in both of the Freaky Friday movies as well).

This approach is akin to the ancient "divide and choose" procedure. That's sometimes known as "you cut, I choose," by which children can evenly divide a cookie between them. A similar approach is often used in so-called "shotgun" buy-sell agreements and in last-offer arbitration; see Protocol 21.11 for a variation. (All these approaches are grounded in the Rawlsian veil of ignorance.)

2.1.7. Freaky-Friday contract terms allow for role-swapping

Here's another potential benefit: On two different occasions, having a Freaky-Friday contract helped BindView get deals done almost immediately when we were the customer, not the vendor:

- On those two occasions, BindView was licensing another vendor's software for our internal use.

- The other vendor wanted to use its own software license agreement, of course. But that license agreement had problems. It would have taken considerable revision and, presumably, legal negotiation for it to work for us as the customer.

- So, we proposed to the vendor that instead we should just use BindView's standard software license agreement — but with BindView as the customer instead of as the vendor. We said we'd be happy to live with the same terms that we asked our customers to accept.

Each time, the other vendor reviewed our license agreement and quickly agreed to our trading-places proposal.

So in the LCP26, we'll use role-swappable terms as our reference benchmarks — as neutral "rules of the road" that contracting parties can agree that they'll follow. We do this on the premise that, when clients negotiate an everyday contract, what they usually want is:

- to get a workable deal done (preferably using a readable contract), with a reliable business partner that has incentives to behave reasonably;

- at a reasonable legal cost and on a reasonable timeline — but sooner is always better;

- at an acceptable level of business risk, with protections appropriate to that risk, without trying to cover every. possible. contingency;

- without trying to play games or big-foot The Other Side;

- while signaling their own reliability as prospective business partners; and

- building trust, not traps.

(All this can run somewhat counter to typical law-school training: We lawyers learn to adopt something of a worst-case, adversarial mindset — and we're often inclined to draft contracts accordingly.)

2.1.8. Counterexample: A Trump building lease backfires

(I wrote this particular section a few months before Donald Trump descended a golden escalator to announce his 2016 presidential campaign.)

The Trump Corporation ("Trump") has been a real-estate landlord, among other things. According to AmLaw Daily, years ago Trump's lawyers took one of the company's leases, changed the names, and used it for a deal in which Trump was the tenant and not the landlord. Later, though, Trump-as-tenant found that its lease-agreement form gave Trump's landlord significant leverage:

"The funny part of it is what one of his internal lawyers must have done years ago," [the landlord's president] says. "Normally Trump is the landlord, not the tenant. So what they did is they took one of their leases and just changed the names. And so it's not a very favorable lease if you're the tenant." Nate Raymond, Trump Misses Rent Payments …, http://goo.gl/B72TIr (AmLawDaily.Typepad.com) (accessed Apr. 27, 2015 but no longer online, not even at archive.org — the site host, Typepad, ceased operations).

Lesson: Contract drafters will often do well to heed advice similar to that of the song Coplas on the Kingston Trio's 1958 debut album, where the in-song patter "translated" the Spanish lyrics into English: Tell your parents not to muddy the water around us: They may have to drink it soon ….

2.1.9. Freaky-Friday terms can be safer for both the parties and the drafters

Role-swappable contract terms can also pay off if the parties' roles ever do get reversed and the business people think that it's safe to use the same contract.

Here's one typical example: In many cases, a two-way confidentiality agreement ("NDA") that protects each party's confidential information is likely to be signed sooner, because:

- each negotiator presumably keeps in mind that today's disclosing party might be tomorrow's receiving party or vice versa; and so:

- the two-way agreement is thus likely — but not guaranteed, see 2.1.10 — to be more balanced;

- moreover, if the parties were ever to switch roles — with the parties agreeing that the original recipient should disclose its own information to the original discloser — then a two-way agreement can avoid (what the original recipient would regard as) disaster, as discussed at 5.3.34.3.

In contrast: With a one-way nondisclosure agreement, only the originally-intended discloser's information is protected. This means that any disclosures by the original recipient might be completely unprotected — resulting in the receiving party's losing its trade-secret rights in its information.

Example: That's pretty close to what happened to one trade-secret owner: The owner had signed a confidentiality agreement with another party, but that agreement protected only the other party's information. Consequently, said the court, the owner's disclosures of its own confidential information were unprotected. See Fail-Safe, LLC v. A.O. Smith Corp. 674 F.3d 889, 893-94 (7th Cir. 2012) (affirming summary judgment for other party).

It's not hard to imagine the thought process that the owner's business people's went through: "We need to disclose our information to you. We've already got an NDA in place. So sure, let's do it." But the NDA didn't do what the plaintiff needed.

(For more about the dangers of unrestricted disclosures of confidential information, see 5.3.11.)

2.1.10. Caution: A supposedly role-swappable draft can be biased

Any agreement that's nominally two-way could still be biased in favor of the drafting party.

Example: Suppose that Fred's drafter knows that Fred will be receiving Ginger's confidential information, but Fred won't be disclosing his own confidential information. In that situation:

- Representing Fred as Recipient, Fred's drafter might write a "two-way" (quote unquote) confidentiality provision that provides very little protection for anyone's confidential information, because that lack of protection won't hurt Fred as Recipient — at least not in the short term.

- Ginger, as Discloser, would therefore have to review the confidentiality provisions carefully to make sure it contained sufficient protection for her Confidential Information.

- Conversely, if Ginger's drafter is doing the drafting — knowing that Ginger will be disclosing her information to Fred, but she won't be receiving Fred's information — then Ginger's drafter might craft the confidentiality provision with burdensome requirements that Fred would have to review carefully.

2.2. Communication

The biggest cause of serious error in this business is a failure of communication. Construction executive Finn O'Sullivan, quoted in Atul Gawande, The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right (2009), at 70.

The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place. (Mis?)attributed to George Bernard Shaw.

Contents:

2.2.1. Business disasters from poor communication

In the world of contracts, parties not communicating has often resulted extra expense — and, sometimes, deadly consequences.

The Healthcare.gov initial rollout: One of the most-embarrassing project failures ever was the initial rollout of the Healthcare.gov Web site to implement the Affordable Care Act (a.k.a. "Obamacare"). One of the root causes was poor communication practice; the successful crash project to fix the site involved frequent communication among developers and other stakeholders. See, e.g., Government Accounting Office, Healthcare.gov[:] Ineffective Planning and Oversight Practices Underscore the Need for Improved Contract Management at 37 (July 2014); Joshua Bleiberg and Darrell M. West, A look back at technical issues with Healthcare.gov (Brookings.edu Apr. 2015); Robinson Meyer, The Secret Startup That Saved the Worst Website in America (TheAtlantic.com 2015); Jennifer Pahlka, Recoding America: Why Government Is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better (2023).

The New York City subway's train-tracking system: A proposed upgrade to the dangerously-antiquated train-tracking system in New York subways ended up grotesquely incomplete and ‑overbudget. "A post-mortem by the Federal Highway Administration details how from the start, an agency which had had little experience with large 'systems' projects tried to wing it. For instance, the consulting firm tasked with developing the project plan … didn’t talk to the workers who would be maintaining the system until after it was designed …." James Somers, Why New York Subway Lines Are Missing Countdown Clocks (The Atlantic.com 2015) (emphasis added).

An extra $100K expense: Here's a less-costly example: In a project to reconstruct a bridge, a subcontractor spent more than $120,000 above the agreed price in trying to resolve an unexpected problem. During ensuing payment litigation, the relevant parties learned that if they'd just talked to one another, they likely would agreed to an alternative approach that would have saved over $100,000 of that extra cost — and that doesn't even take into account the time and money the parties spent in litigation. See Construction Drilling, Inc. v. Engineers Construction, Inc., 2020 VT 38 ¶¶ 6-7, 236 A.3d 193, 196-97 (2020) (affirming denial of subcontractor's breach-of-contract claim).

2.2.2. Worse: Death and destruction

When parties don't communicate, it can sometimes result in death, injury, and property damage. The world has seen tragic examples of failures in this regard:

– The 2025 Potomac River mid-air collision between an Army Black Hawk helicopter and an American Airlines commuter flight, killing all 67 people aboard both aircraft;

– The Three Mile Island nuclear accident;

– The Hyatt Regency walkway collapse;

– Hurricane Katrina's ravaging of New Orleans.

All were caused at least in part by communications failures.

Professionals working in these and related fields are (with any luck) trained in experience-based lessons history that, as pilots say, have often been "written in blood." Gary S. Rudman, Checklist mentality … it’s a good thing (safety.af.mil 2012).

2.2.3. Benefits of regular, structured communications

Outcomes can be greatly improved — and sometimes, catastrophe averted — by habits of pre-planned communications, such as:

- aircraft pilots check in with air traffic control at standard points in their flights;

- in surgeries, the surgeons announce to their teams what they're doing;

- in nuclear reactor operations, watchstanders at various equipment stations inform the central control desk whenever they're about to change configurations.

This is a subtext of the 2009 book The Checklist Manifesto (highly recommended reading, by way), by surgeon, Rhodes scholar, and MacArthur "genius grant" recipient Atul Gawande, M.D. That book grew out of Gawande's 2007 article in The New Yorker, recounting his visit to the construction site of the Russia Wharf, a 32-floor building in Boston (now called the Atlantic Wharf).

In that visit, Gawande learned that particular, time-specific communications were an important feature of the checklists used by the general contractor's construction executives:

While no one could anticipate all the problems, they could foresee where and when they might occur. The checklist therefore detailed who had to talk to whom, by which date, and about what aspect of construction —who had to share (or 'submit') particular kinds of information before the next steps could proceed.

The submittal schedule specified, for instance, that by the end of the month the contractors, installers, and elevator engineers had to review the condition of the elevator cars traveling up to the tenth floor.

The elevator cars were factory constructed and tested. They were installed by experts. But it was not assumed that they would work perfectly. Quite the opposite.

The assumption was that anything could go wrong, anything could get missed. What? Who knows? That’s the nature of complexity.

But it was also assumed that, if you got the right people together and had them take a moment to talk things over as a team rather than as individuals, serious problems could be identified and averted. Id. at 65-66; emphasis and extra paragraphing added.

To be sure: In many types of contract, such intensive communication might well be costly overkill. But more often, the problem is too little communication.

2.3. Form follows function (or should, at least)

The goal of any contract is to remind the parties — and persuade them?

Contents:

2.3.1. Contracts are for people, not computers

The author of a popular contract style manual once opined — wrongly — that, apart from the opening recitals, "in a contract you don’t reason or explain. You just state rules." Ken Adams, More Words Not to Include in a Contract— “Therefore” and Its Relatives, at http://www.adamsdrafting.com/therefore/ (2008).

That view would be fine — if it weren't for a few inconvenient facts:

- Even in a business-to-business contract, it's people, not computers, who carry out obligations and exercise contract rights. Computers do exactly as they're told, but people? Not so much — at least not always reliably. (Note: So-called digital "smart contracts" are a very-different thing.)

- People can forget (sometimes "conveniently") what was agreed to before. This can be especially true when individuals' personal incentives — which often are hidden — are involved (see 27.3).

- As time goes on, people (and thus parties) can change their minds about what they regard important. "Buyer's remorse" is just one example of this phenomenon.

- A contracting party's circumstances can change after the contract is signed. If that happens, the party might want (or desperately need) to back out of the deal — see, e.g., Elon Musk's unsuccessful attempt to abandon his agreement to acquire Twitter.

- The people who originally negotiated the business terms might not be in the same jobs. Their successors might not know why the parties agreed to the terms that they did. And again, the successors might have a different view of what's important and which obligations to honor.

2.3.2. People sometimes need to be reminded — or persuaded

The upshot: The people who will carry out a contract will sometimes need to be reminded — or even persuaded — to do the specific things called for by a contract. (Examples and explanations, see 20.21.4.1, possibly stated in footnotes, see 8.20, can serve as useful reminders on that score.)

To be sure, the famous Strunck & White drafting guide counsels writers to "omit needless words." But the operative word there is needless. The contract drafter's mission includes helping remind the parties what they agreed to — and if necessary, to help persuade them to act accordingly. Sometimes, a few extra words of explanation in a contract can help.

2.3.3. Future readers will need to be brought up to speed

Let's not forget another important group of future readers: Judges, jurors, and arbitrators will sometimes be asked to enforce a contract in a lawsuit or arbitration. The vast majority of contracts never see the inside of a courtroom, but drafters must think about the possibility — again, without going overboard or putting the client in the position of being scared of its own shadow.

– Clarity is the first criterion: It's much easier for a court to grant an early motion to dismiss a bogus contract claim if the contract language itself refutes the claim. [DCT TO DO: Pick an example.] Likewise, if a contract clearly states that A must take Action X, and A doesn't do so, then a court is more likely to grant at least partial summary judgment on liability.

– Tone can be a factor: Like all of us, judges and jurors can be influenced by what they think is "fair." Sometimes, the phrasing of a contract's terms can make a difference in how judges and jurors react to the parties and to the positions they're taking. (We'll see examples during the semester.)

For both clarity and tone, sometimes a few extra words can pay off. How much is "a few" is a matter of judgment to be addressed case-by-case — when in doubt, Ask the Partner! (30.5).

2.4. The Great Rule: Serve the Reader!

The hallmark of good legal writing is that an intelligent layperson will understand it on the first read. Judge Gerald Lebovits, Free at Last from Obscurity: Achieving Clarity, 96 Mich. B.J. 38 (May 2017), SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2970873.

"To serve the client, serve the reader!" should be The Great Rule of All Legal Writing — keeping mind that clients on both sides of the table would often prefer not to be reading the contract at all: They have other things on their minds — such as getting the deal "done" and moving on to other matters — and so they're frequently un-fond of having to spend time on reading the "legalese" terms and conditions.

Contracts written in dense legalese are less effective at educating or persuading readers — and those are two key missions of every contract drafter. But who is the reader? There are many possibilities — both now and in the future:

- business people who need to get up to speed for negotiating the contract;

- business people who have to carry out the contract's obligations — and those might not be the same business people who were involved in the contract negotiation, so they might well be reading the contract "cold";

- lawyers for one or both parties, possibly new to representing their respective clients;

- (unfortunately sometimes:) judges and jurors.

Apropos of that last point: Certainly the vast majority of contracts never see the inside of a courtroom. But it can't hurt to do some little things to plan for that possibility, as long as it won't increase costs or delay getting to signature, because:

- Courts are more likely to enforce clear terms. Example: A former employee sued a company — after having signed a severance agreement that included release language. The court granted the company's motion for judgment on the pleadings, noting that "[t]he Agreement is stated in clear and unmistakable terms that are understandable to the average individual. Accordingly, the release is enforceable …." Makarevich v. USI Ins. Services, LLC, No. 1:25-cv-10434-JEK, part I, slip op. (D. Mass. Jul. 14) (granting judgment on the pleadings against pro se former employee, but with leave to amend as to any post-release claims) (emphasis added); see also order of dismissal (Aug. 5, 2025).

- Trial counsel prefer plain language in a contract, because plain language offers better "sound bites" for trial exhibits and for use in cross-examining witnesses.

- Plain contract language can help guide the jury in jury deliberations because the contract will normally be part of the "real" evidence in the record that the jury gets to review — the same won't always be true of trial counsel's demonstrative exhibits (summaries, PowerPoint slides, etc.) that the judge might or might not allow to be taken back into the jury room.

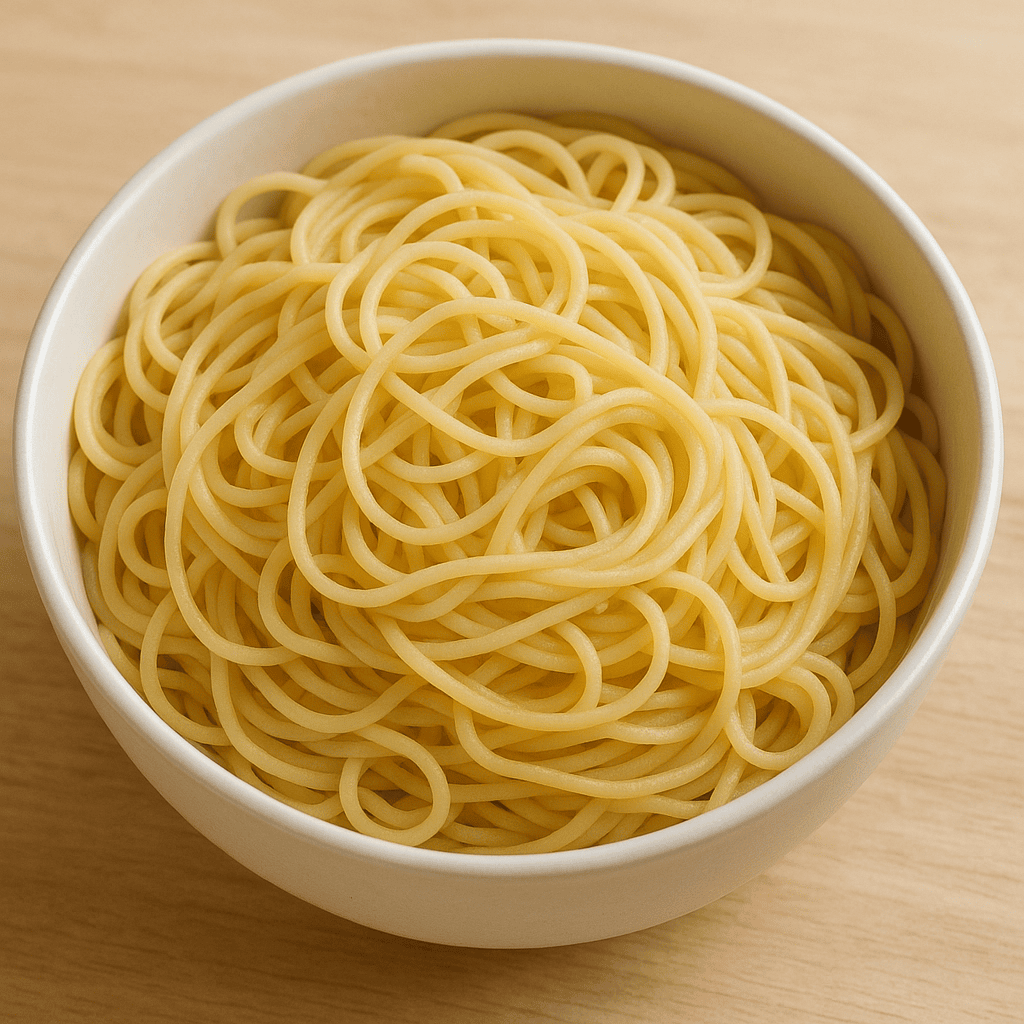

2.5. The Spaghetti Rule: Short, single-subject paragraphs

Contents:

2.5.1. Avoid "spaghetti" clauses!

Surely you've read contract provisions that are written as long, tangled skeins of legalese. Let's call them "spaghetti clauses."

(In the software world, "spaghetti code" is a mildly-contemptuous epithet for unstructured, hard-to-maintain source code for computer programs, sometimes also known as "rat's nests" or "big balls of mud," as opposed to more-modular "ravioli code" or "macaroni code.") See generally Spaghetti code (Wikipedia.org).

As an example: Just glance at the following two-sentence excerpt from an airline merger agreement — 309 words in the first sentence and 64 words in the second one:

[4.3] (b) Neither the execution and delivery of this Agreement by Continental nor the consummation by Continental of the transactions contemplated hereby, nor compliance by Continental with any of the terms or provisions of this Agreement, will[:] (i) assuming (solely in the case of the Merger) that the Continental Stockholder Approval is obtained, violate any provision of the Continental Charter or the Continental Bylaws or (ii) assuming that the consents, approvals and filings referred to in Section 4.4 are duly obtained and/or made, (A) violate [x] any Injunction or, [y] assuming (solely in the case of the Merger) that the Continental Stockholder Approval is obtained, any statute, code, ordinance, rule, regulation, judgment, order, writ or decree applicable to Continental, any of the Continental Subsidiaries or any of their respective properties or assets or (B) violate, conflict with, result in a breach of any provision of or the loss of any benefit under, constitute a default (or an event which, with notice or lapse of time, or both, would constitute a default) under, result in the termination of or a right of termination or cancelation under, accelerate the performance required by, or result in the creation of any Lien upon any of the respective properties or assets of Continental or any of the Continental Subsidiaries under, any of the terms, conditions or provisions of any note, bond, mortgage, indenture, deed of trust, Continental License, license, lease, agreement or other instrument or obligation to which Continental or any of the Continental Subsidiaries is a party, or by which they or any of their respective properties or assets may be bound or affected, except, in the case of clause (ii), for such violations, conflicts, breaches, defaults, terminations, rights of termination or cancelation, accelerations or Liens that would not, individually or in the aggregate, reasonably be expected to have a Material Adverse Effect on Continental. Without limiting the generality of the foregoing, as of the date of this Agreement, Continental is not a party to, or subject to, any standstill agreement or similar agreement that restricts any Person from engaging in negotiations or discussions with Continental or from acquiring, or making any tender offer or exchange offer for, any equity securities issued by Continental or any Continental Voting Debt. From https://tinyurl.com/UAL-CAL (SEC.gov); bracketed lettering added — not that it helps much. See more before-and-after examples at the Digital.gov site.

This isn't just a question of aesthetic taste: The harder it is to read and understand a draft contract:

- the longer it will take — and the more it will cost — for the parties to review (certainly), revise (probably), and sign it; and

- the greater the odds that a future reader might "misunderstand" the language — perhaps intentionally so.

2.5.2. Go for scanability: One substantive point per short paragraph

Each paragraph in a contract should be short AND address a single point that might require significant discussion. If that means spinning off some of the draft verbiage into separate paragraphs, then so be it. Other things being equal:

- Short paragraphs are easier for The Other Side to review. That will help speed up getting the contract to signature, which your client will almost always appreciate. (It might also earn your client just a bit of goodwill from The Other Side.)

- Short paragraphs are better workaday tools for business managers, and, if necessary someday, for trial counsel and judges.

- In the future, short paragraphs can be more-easily copied and pasted into a different contract without inadvertently messing up some other clause.

As a federal-government plain language guide explains:

Short paragraphs are easier to read and understand. Long paragraphs can discourage users from trying to understand your material.

* * *

There is nothing wrong with an occasional one-sentence paragraph.

Using short paragraphs is an ideal way to open up your writing and create white space. In turn, this makes your writing more inviting and easier to read. …

* * *

Limit each paragraph or section to one topic. This makes it easier for your audience to understand your information. Each paragraph should start with a topic sentence that captures the essence of everything in the paragraph.

Putting each topic in a separate paragraph makes your information easier to digest.

So: Do this when drafting a contract:

1. Write as many short sentences and paragraphs — "sound bites," if you will — as are needed to cover the subject.

2. If a sentence starts to run too long for easy reading — and we all do it — then break it up. Do likewise for run-on paragraphs.

Students: In our Contract Drafting course we'll do a number of in-class exercises where you'll work together in small groups to break up some real-world spaghetti clauses.

Even if the resulting draft happens to take up a few extra pages, your client likely will thank you for it.

To be sure: Short paragraphs weren't always welcome: In the days when contracts were printed out in hard copy, many lawyers intentionally used a "compressed" format — narrow margins, long paragraphs, small print — so as to fit on fewer pieces of paper.

But those days are long gone. Nowadays, pretty much everyone reviews and even signs contracts on a screen, not on paper. So the page length is far less important to negotiation than the readability of the text.

2.5.3. Background: Why do lawyers draft spaghetti clauses?

A holdover from lawyers dictating to secretaries? In traditionally-drafted contracts, the spaghetti-clause style (see 2.5.1) might well have come from the way lawyers drafted contracts, letters, etc., in the days before desktop computers and word-processing software.

When I was a brand-new lawyer, I knew a couple of ancient attorneys — or at least I thought they were ancient; I'm probably older now than they were then — who still dictated contract language to a secretary:

The secretary would take down the lawyer's words on a stenographer's pad, often using Pitman or Gregg shorthand.

(Sometimes the attorney would instead use a tape recorder such as a Dictaphone and give the tape to the secretary to type up.)

- If in mid-dictation the lawyer was struck by a new thought, he might well say, "semicolon; provided, however, that …."

- The secretary would type up the lawyer's dictation on a typewriter — generally with no memory features, and likely with "flimsies" (carbon paper sets) to make additional copies.

- Any editing of typed drafts had to be done with typewriter erasers and/or Wite-Out or Liquid Paper correction fluid.

- Retyping was time-consuming and costly; you really didn't want to have to do it if you could avoid it.

So it's easy to see how spaghetti paragraphs came to be regarded as acceptable, even as a standard of practice. Ditto for "provided, however" interruptions in spaghetti paragraphs.

In the modern era, though: While anyone might sometimes draft a spaghetti clause, there's no excuse for leaving it that way instead of breaking up the clause into shorter sound bites.

Too busy? Another possible explanation comes from famed French sage Blaise Pascal, paraphrased in English as: "If I'd had more time, I'd have shortened this letter." Blaise Pascal, Lettre XVI, in Lettres provinciales, Letter XVI (Thomas M'Crie trans. 1866) (1656), available at https://tinyurl.com/PascalLetterXVI (WikiSource.org).

(That paraphrase is itself a simplification of Pascal's original, which could be translated as, "I made this-here [letter] longer because I haven't had the leisure to make it shorter.")

Like Pascal, contract drafters are usually time-constrained, having to juggle multiple projects. So they often don't really think about whether they're hurting their clients' interests by making their work less-readable.

Caution: Is a L.O.A.D. trying to sneak in an unfavorable term? For some spaghetti clauses, there might be a less-innocent explanation: Is it possible that a L.O.A.D. — a Lazy Or Arrogant Drafter — was secretly hoping to use the MEGO factor ("Mine Eyes Glaze Over") to sneak an objectionable term past the other party's contract reviewer? This actually happens sometimes. For example, in the estimable redline.net forum (for lawyers only, membership required):

- A lawyer recounted how he once represented a novice writer who was looking for an agent, to help the writer deal with publishers, etc.

- One agency expressed interest in representing the writer and sent over a contract for the writer to sign.

- But: Buried in a long paragraph was language to the effect that any work that the writer produced while the agency was representing the writer would be owned by the agency (!!!), not the writer.

The lawyer naturally advised the writer, "DO NOT SIGN."

Is the drafter trying to feel more important? Some less-secure lawyers might imagine that by using dense legalese, they'll enhance their personal prestige as High Priests of the Legal Profession, privvy to secret legal knowledge that's out of ordinary mortals' reach. That seems a dubious proposition at best — and indeed a risible one.

2.6. The BLUF Rule: Bottom Line Up Front!

A useful rule of readability, borrowed from the U.S. military, is BLUF: Bottom Line Up Front. See, e.g., Kabir Sehgal, How to Write Email with Military Precision (HBR.com 2016), archived at https://perma.cc/B986-5DUY; the byline indicates that the article's author is a U.S. Navy veteran.

Contents:

2.6.1. Use BLUF for even slightly-longish clauses

Here's a contract provision that was litigated in a state court; following the lead of the famous Where's Waldo? children's books, let's play a short game of Where's the Action Verb? and then see if we can make it more readable:

BEFORE: (just scan this — there's no need to read it)

If any shareholder of the corporation for any reason ceases to be duly licensed to practice medicine in the state of Alabama, accepts employment that, pursuant to law, places restrictions or limitations upon his continued rendering of professional services as a physician, or upon the death or adjudication of incompetency of a stockholder or upon the severance of a stockholder as an officer, agent, or employee of the corporation, or in the event any shareholder of the corporation, without first obtaining the written consent of all other shareholders of the corporation shall become a shareholder or an officer, director, agent or employee of another professional service corporation authorized to practice medicine in the State of Alabama, or if any shareholder makes an assignment for the benefit of creditors, or files a voluntary petition in bankruptcy or becomes the subject of an involuntary petition in bankruptcy, or attempts to sell, transfer, hypothecate, or pledge any shares of this corporation to any person or in any manner prohibited by law or by the By-Laws of the corporation or if any lien of any kind is imposed upon the shares of any shareholder and such lien is not removed within thirty days after its imposition, or upon the occurrence, with respect to a shareholder, of any other event hereafter provided for by amendment to the Certificates of Incorporation or these By-Laws, [ah, here we finally get to the (wordy) "bottom line"] then and in any such event, the shares of this [c]orporation of such shareholder shall then and thereafter have no voting rights of any kind, and shall not be entitled to any dividend or rights to purchase shares of any kind which may be declared thereafter by the corporation and shall be forthwith transferred, sold, and purchased or redeemed pursuant to the agreement of the stockholders in [e]ffect at the time of such occurrence. The initial agreement of the stockholders is attached hereto and incorporated herein by reference[;] however, said agreement may from time to time be changed or amended by the stockholders without amendment of these By-Laws. The method provided in said agreement for the valuation of the shares of a deceased, retired or bankrupt stockholder shall be in lieu of the provisions of Title 10, Chapter 4, Section 228 of the Code of Alabama of 1975. From Lynd v. Marshall County Pediatrics, P.C., 263 So. 3d 1041, 1044-45 (Ala. 2018) (emphasis added).

This kind of writing brings to mind a savagely-funny Dilbert cartoon about lawyers.

Let's take a stab at converting the above spaghetti paragraph into short-BLUF format:

BEFORE: See above.

AFTER: (just scan this)

(a) A shareholder's relationship with the corporation will be terminated, as specified in more detail in subdivision (b), if any of the following Shareholder Termination Events occurs:

(1) the shareholder, for any reason, ceases to be duly licensed to practice medicine in the state of Alabama;

(2) the shareholder accepts employment that, pursuant to law, places restrictions or limitations upon his continued rendering of professional services as a physician

[remaining subdivisions omitted]

(b) Immediately upon the occurrence of any event described in subdivision (a), that shareholder's shares:

(1) will have no voting rights of any kind,

[Remaining subdivisions omitted]

(Emphasis added.)

Surely the AFTER: version is the more readable of the two?

An even-worse example is reproduced in the footnote — masochists are welcome to read it, but others are free to skip it.1

2.6.2. Client benefit: BLUF clauses are more memorable

Researchers at MIT conducted an experimental study (led by a career-changing Harvard law graduate) of legalese comprehension. The study's results pointed to a chief villain in legalese: "center-embedded clauses" — i.e., sentences and paragraphs where the action verb is buried in a spaghetti paragraph (see 2.5). The researchers found that such clauses "inhibited recall to [an even] greater degree than other features" such as jargon and passive voice. Eric Martínez, Francis Mollica, and Edward Gibson, Poor writing, not specialized concepts, drives processing difficulty in legal language, Cognition (2022).

2.6.3. Example: A real-world contract clause in need of BLUF work

As another illustration, here's an example of a spaghetti clause that's in serious need of rework; it's from the merger agreement by which Hewlett-Packard (HP, Inc.) acquired well-known headset manufacturer Plantronics.

(Students, you can just skim this to get the idea.)

BEFORE:

SECTION 6.07 Indemnification and Insurance. (a) All rights to indemnification, exculpation from liabilities and advancement of expenses for acts or omissions occurring at or prior to the Effective Time now existing in favor of any individual (i) who is or prior to the Effective Time becomes, or has been at any time prior to the date of this Agreement, a present or former director or officer (including any such individual serving as a fiduciary with respect to an employee benefit plan) of the Company or (ii) in his or her capacity as a present or former director or officer of one or more of the Company Subsidiaries as of the date of this Agreement (each such individual in (i) and (ii), an “Indemnified Person”) as provided in, with respect to each such Indemnified Person, as applicable, (i) the Company Charter, (ii) the Company Bylaws, (iii) the organizational documents of any applicable Company Subsidiary in effect on the date hereof at which such Indemnified Person serves as a director or officer, as applicable, or (iv) any indemnification agreement, employment agreement or other agreement made available to Parent, containing any indemnification provisions between such Indemnified Person, on the one hand, and the Company and the Company Subsidiaries, on the other hand, [ah, here comes the action verb, finally!] shall survive the Merger in accordance with their terms and shall not be amended, repealed or otherwise modified in any manner that would adversely affect any right thereunder of any such Indemnified Person with respect to acts or omissions occurring at or prior to the Effective Time.

Let's rewrite subdivision (a) above, without using spaghetti and following the BLUF Rule:

- Short paragraphs, with just one negotiation point per paragraph — no spaghetti paragraphs; and

- Bottom Line Up Front.

Oh, and while we're at it, let's help guide the reader's eye by (judiciously) bold-facing a few key words:.

AFTER: (just skim this)

SECTION 6.07 Indemnification and Insurance.

(a) See subdivision (c) below for definitions of particular capitalized terms. [Comment: Note the forward reference to subdivision (c).]

(b) If before the Effective Time, an Indemnified Person was entitled to Protection, then after the Effective Time, that person will continue to be entitled to Protection in the same manner as before.

(c) Definitions: For purposes of this section 6.07:

"Company Entity" refers to each of the following: (1) the Company; and (2) any of the Company Subsidiaries existing as of the date of this Agreement.

"Indemnified Person" refers to any individual who is, or prior to the Effective Time becomes, or has been at any time prior to the date of this Agreement, in one or more of the following categories:

(1) a present or former director or officer of any Company Entity; and/or

(2) any individual serving as a fiduciary with respect to an employee benefit plan of any Company Entity.

"Protection," with respect to an Indemnified Person, refers to the Indemnified Person's right to be indemnified; to be released from liability; and/or to have expenses advanced; as provided in one or more "Protection Documents" (see below).

"Protection Document" refers to each of the following, as applicable:

(1) the Company Charter;

(2) the Company Bylaws;

(3) the organizational documents of any applicable Company Entity;

(4) any agreement — including, without limitation, any indemnification agreement and/or employment agreement — that (A) establishes one or more rights to Protection for the Indemnified Person, and (B) was made available to Parent prior to the Effective Time.

Is there any doubt which version would be easier to read, understand, negotiate, and revise? Clearly, it's the After version.

And imaging the reader's task in reviewing and thinking about the Before version ….

2.7. Looking ahead to the Age of AI

Computer programs known as artificial intelligence, or "AI," are doing more contract drafting and contract review. And it's not just lawyers who are using AIs: It can be a lot less expensive for a client to have an AI generate a contract, or to review another party's contract draft, than to pay a lawyer to do it. For an everyday‑ or low-impact transaction, the client might well decide that this is an acceptable business risk. (I've begun to see glimpses of this in my own part-time law practice.)

This increasing use of AIs presents some challenges for law schools and law firms:

- AI programs require human oversight, because those programs can sometimes "hallucinate." For example: In the courtroom arena, numerous lawyers have found themselves in trouble because they submitted AI-drafted briefs contaning bogus citations. This famously includes President Trump's former personal lawyer Michael Cohen when he sought a reduction in his prison sentence and supervised release.2

3. General provisions

This chapter describes good-practice ground rules that are usually included in a contract's general-provisions article toward the end.

Contents:

- 3.1. Amendments in Writing Protocol

- 3.2. Catch-Up Calls Protocol

- 3.3. Entire Agreement Protocol

- 3.4. Escalation (Internal) Protocol

- 3.5. Exclusivity Explicitness Protocol

- 3.6. Government Subcontract Disclaimer Protocol

- 3.7. Incorporation by Reference Protocol

- 3.8. Independent Contractors Protocol

- 3.9. Lawyer Involvement Protocol

- 3.10. Legal Review Confirmation Protocol

- 3.11. Letter of Intent Protocol

- 3.12. Material-Problems Disclosure Protocol

- 3.13. No-Conflict Confirmation Protocol

- 3.14. Notices Protocol

- 3.15. Signature Document Integrity Protocol

- 3.16. Signature Mechanics Protocol

- 3.17. Signer Personal Confirmation Protocol

- 3.18. Waivers in Writing Protocol

- 3.19. Certain defined terms

3.1. Amendments in Writing Protocol

Contents:

3.1.1. Prerequisite: Signed writing with clear title

What must happen to amend the Contract?

An amendment to the Contract is effective and binding only if all of the following requisites are met:

- 1. Each change to the Contract is clearly stated in a written modification document.

- 2. At least one of the following is true:

- a. The modification document is clearly titled as an amendment; and/or

- b. The circumstances unmistakably indicate that each bound party knew that the modification document was changing the Contract.

- 3. The modification document is signed by the party that is supposedly bound by the amendment.

Note

(). Subdivision 1: It's extremely common for contracts to require amendments to be in writing, to try to avoid "he said, she said" disputes in the future. But: In some jurisdictions, a court might disregard a writing requirement; this is discussed in more detail at 10.5.4.1. (This is addressed at § 3.1.3 below.)

Subdivision 2: If a document purports to be an "amendment," that fact should be immediately obvious to the reader. Otherwise, a party to a contract might (opportunistically) claim that some random document was, surprise!, an amendment to the contract — which has led to costly litigation.

Example: The buyer of an office complex tried, and failed, to assert that an estoppel certificate, signed by a tenant, had modified the tenant's lease. See Expo Properties, LLC v. Experient, Inc., 956 F.3d 217, 224 (4th Cir. 2020) (affirming summary judgment).

Providing a clear amendment title follows the Great Rule of Contract Drafting, namely To serve the client, serve the reader! (2.4). Drafters shouldn't assume that a party would spot a contract amendment that was contained in some other type of document that the party was being asked to sign.

The Contract could allow unilateral amendments by notice as provided in Protocol 15.1.

Subdivision 2: Certainly it's better if all parties sign an amendment document. But ordinarily in the U.S., the law requires only the signature of the party that's supposedly bound by the amendment. Example: The Seventh Circuit once noted: "The critical signature [in an amendment] is that of the party against whom the contract is being enforced, and that signature was present." (Emphasis added.) Hess v. Kanoski & Assoc., 668 F.3d 446, 453 (7th Cir. 2012) (emphasis added).

Relatedly: Under the (U.S.) Uniform Commercial Code's statute of frauds provision in UCC § 2-201, a written contract (for the sale of goods) must be signed "by the party against whom enforcement is sought …."

And: Here's a potential footgun: If a contract states that amendments must be signed by all parties, then a missing signature could render the entire amendment unenforceable, even if the omission was inadvertent. This was the result in more than one court case, illustrating the R.O.O.M. principle — Root Out Opportunities for Mistakes (or Misunderstandings. (Or if you prefer: R.O.O.F.: Root Out Opportunities for F[oul]-ups.)

Example: In Expo Properties, cited above, the tenant's lease explicitly required both the tenant and the landlord to sign any proposed amendments of the lease — but the "estoppel certificate" in question had been signed by the tenant only, so the lease was not modified to be more favorable to the landlord.

Example: JPMorgan Chase lent money to a borrower. The loan agreement specifically said that both parties were required to sign any modification. The borrower claimed that the loan agreement had been modified — but the court said that the modification was ineffective because JPMorgan Chase never did countersign it. See Taylor v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, NA, 958 F.3d 556 (7th Cir. 2020) (affirming summary judgment).

3.1.2. Prerequisite: Minimum signature authority

Who is authorized to sign an amendment for a party?

If A signs an amendment, then the amendment is binding on A if all of the following prerequisites are met:

☒ 1. The signature was by an individual who had apparent authority to sign on A's behalf.

☒ 2. The Contract itself does not clearly limit who can sign amendments for A.

☒ 3. B did not have other reason to know that the individual (the signer) did not actually have signature authority.

Note

A contract between A and B might explicitly limit who is allowed to sign amendments on behalf of A — this is to put B on notice that others individuals don't have authority to sign for A, even if the doctrine of "apparent authority" might suggest otherwise. See 29.5.3 for more discussion.

3.1.3. Claims of non-written amendments

The Writing-Requirement Challenges Protocol (10.5) is incorporated by reference as part of this Protocol.

3.1.4. Additional notes

Contents:

- 3.1.4.1. Amendments vs. waivers

- 3.1.4.2. Pro tip: Consider an "amended and restated agreement" instead

- 3.1.4.3. Pro tip: Consider an amendment number and date

- 3.1.4.4. Pro tip: Drafting signature blocks for amendments

- 3.1.4.5. Other reading about amendment signatures

- 3.1.4.6. Caution: Does the amendment include a release?

- 3.1.4.7. Caution: Could there be other unwanted side effects?

- 3.1.4.8. Make sure to file the signed amendment!

- 3.1.4.9. Caution: A casual writing could amend a contract

- 3.1.4.10. Caution: A text-message amendment could be problematic

- 3.1.4.11. Is there sufficient "consideration" for the amendment?

- 3.1.4.12. Special case: Sales of goods under the UCC

3.1.4.1. Amendments vs. waivers

Parties considering an "amendment" to the Contract should consider whether what they really want is simply one party's waiver (see Protocol 3.18) of a particular right or obligation.

According to Black's Law Dictionary (the canonical English-language legal dictionary), an amendment is "[a] formal and usu. [usually] minor revision or addition proposed or made to a statute, constitution, pleading, order, or other instrument …."

Here's a hypothetical example: Imagine a contract between Alice and Bob. Suppose that the contract calls for Bob to take care of Alice's lawn; Bob's obligations include mowing the lawn each week, raking leaves in the autumn, etc.

Now suppose that on one particular day, Alice comes outside to talk to Bob when she arrives to mow the lawn.

- If Alice says, "Hi Bob — I don't need the lawn mowed this week." That's known as a waiver, by Alice, of Bob's obligation for that occasion.

- Or, Alice might say, "never mind, Bob, I don't need you to mow the lawn ever, because my teen-aged son wants to do it from now on — so let's talk about changing the contract to reduce what you have to do and also reduce what I pay you." If Bob agrees, that's known as an amendment of their contract.

3.1.4.2. Pro tip: Consider an "amended and restated agreement" instead

Drafters: If you'll be making extensive changes to a contract — or if there have already been multiple amendments to the same contract over time — then consider doing a complete "amended and restated" agreement, with that title.

Example: The title of one Enterprise Products Partners limited-partnership agreement is, "Seventh Amended and Restated Agreement of Limited Partnership of Enterprise Products Partners L.P." (emphasis added).

Caution: If doing an amended-and-restated agreement, you'll want to consider whether you could be wiping out a provision that your client might later want to rely on. Example: That was the result in a case where:

- an earlier contract contained a payment guaranty;

- an amended and restated contract didn't contain the guaranty.

Presumably this was to the chagrin of the creditor that, as a result, didn't get paid. See Electronic Merchant Systems v. Gaal, 58 F.4th 877 (6th Cir. 2023) (affirming dismissal of creditor's suit against guarantor for failure to state a claim).

3.1.4.3. Pro tip: Consider an amendment number and date

In the amendment's title, strongly consider including a series number and date — and perhaps even include a (brief) mention of the amendment's purpose — to leave a paper trail, reduce the chances of confusion, and make it easier for a reader to find the amendment when skimming a list of document titles.

Example:

✘ Amendment

✓ Amendment No. 1 to Asset Purchase Agreement (Increase of Purchase Price)

If making further amendments to Amendment No. 1 itself, consider:

✘ Amendment No. 1 to Amendment 1 to Asset Purchase Agreement ….

✓ Amendment No. 1.1 to Asset Purchase Agreement ….

This is especially important to consider when multiple amendments have occurred. Example: The members of a limited-liability company ("LLC") agreed to amend the LLC's operating agreement when its managing member resigned — that amendment was the ninth one. See Paul v. Rockport Group, LLC, No. 2018-0907-JTL (Del. Ch. Jan. 9, 2024) (granting summary judgment in favor of plaintiff, the LLC's former managing member).

3.1.4.4. Pro tip: Drafting signature blocks for amendments

3.1.4.5. Other reading about amendment signatures

3.1.4.6. Caution: Does the amendment include a release?

Sometimes a contract will be amended to resolve a disagreement between the parties. If that happens, a release might be drafted so broadly as to cause other rights to vanish.

Example: In a federal-government contracting case, fact issues precluded summary judgment whether a contract modification had effected a release of certain other claims, so that the contractor would be barred from asserting those other claims against the government. (The parties settled the case three months thereafter.) See Fortis Indus., LLC v. GSA, CBCA 7967, slip op. at 4-5 (Sept. 18, 2024), settled (Jan. 29, 2025).

3.1.4.7. Caution: Could there be other unwanted side effects?

Drafters of amendments should watch out for possible unwanted "side effects," in which an amendment to one provision turns out to affect one or more other provisions as well. This can be a particular problem when defined terms are used, as discussed in Kidd (stephens-bolton.com, undated).

This, incidentally, is one reason for contract drafters to follow the D.R.Y. Principle (see at 30.4) — that is, Don't Repeat Yourself, usually — to try to reduce such intra-draft "dependencies," and thus the possibility for inconsistent revisions to the draft during negotiations.

3.1.4.8. Make sure to file the signed amendment!

In ongoing business relationships, contracts might be amended multiple times. At some point in the future, it might be easy to overlook a previously-signed amendment — and then be caught by surprise in a future discussion (friendly or otherwise).

For that reason, parties should save any signed amendment document in a place where it will be noticed by later readers of the contract. (This should be a routine thing for businesses already.)

3.1.4.9. Caution: A casual writing could amend a contract

Technically, a binding written document amending the Contract could be an exchange of emails — or even an exchange of text messages. Example: In a lawsuit between a digital ad agency and one of its clients, an e-cigarette manufacturer, an IM exchange resulted in the manufacturer's having to pay the agency more than $1 million in additional fees:

- The crux of the IM exchange started with a message from an account executive at the ad agency: "We can do 2000 [ad placement] orders/day by Friday if I have your blessing."

- The e-cigarette manufacturer's VP of advertising responded: "NO LIMIT"

- The ad agency's account executive responded: "awesome!"

That series of messages served to modify the parties' contract; as a result, the e-cigarette manufacturer had to pay the ad agency the additional fees. See CX Digital Media, Inc. v. Smoking Everywhere, Inc., No. 09-62020-CIV, slip op. at 8, 17-18 (S.D. Fla. Mar. 23, 2011).

3.1.4.10. Caution: A text-message amendment could be problematic

A text-message amendment might not be a good idea because:

- it might be overlooked by the relevant business people (see 3.1.4.8);

- it might disappear; and

- even if it didn't disappear, it might be legally ineffective in some jurisdictions, as discussed at 28.3.3.

Similarly, writing and signing an amendment on something like a Post-It note would be inadvisable, even though technically it'd be binding if it was otherwise sufficient.

3.1.4.11. Is there sufficient "consideration" for the amendment?

Applicable law might require "consideration" (see 32.7) for amendments to existing contracts. Generally speaking, this means that each side gets at least some benefit from the amendment.

3.1.4.12. Special case: Sales of goods under the UCC

In Article 2 of the (U.S.) Uniform Commercial Code — which in general applies to transactions that are predominantly for the sale of goods — section 2-209(2) provides as follows:

(1) An agreement modifying a contract within this Article needs no consideration to be binding.

(2) A signed agreement which excludes modification or rescission except by a signed writing cannot be otherwise modified or rescinded, but except as between merchants [basically, regular buyers and sellers of goods of the kind] such a requirement on a form supplied by the merchant must be separately signed by the other party.

(3) The requirements of the statute of frauds section of this Article (Section 2-201) [which requires certain contracts to be in writing] must be satisfied if the contract as modified is within its provisions.

(4) Although an attempt at modification or rescission does not satisfy the requirements of subsection (2) or (3) it can operate as a waiver.

(5) A party who has made a waiver affecting an executory portion [i.e., a not-yet-started portion] of the contract may retract the waiver by reasonable notification received by the other party that strict performance will be required of any term waived, unless the retraction would be unjust in view of a material change of position in reliance on the waiver.

3.2. Catch-Up Calls Protocol

Many clients would be pleased if their contract relationships could look a bit like what they see in many (fictional) TV dramas: Serious, competent professionals who team up in the service of common goals; collaboratively deal with disagreements and other adversities together; and with any luck, start to develop trusted, collegial relationships.

(Cue the Beach Boys: Wouldn't it be nice, to [work] together ….)

Contents:

3.2.1. Frequency of calls

How often must we do catch-up calls?

Under this Protocol: Each party participates in a catch-up call as stated in this Protocol whenever any party reasonably asks — for example, to deal with problems and/or ‑opportunities (existing or anticipated).

Note

(). Regular communication can be one of the best ways of keeping business dealings on track, as discussed at 2.2. For that reason, parties should consider discussing whether to schedule regular catch-up calls.

This is structured as a "Rule" because the "whenever any party reasonably asks" limitation would automatically impose a natural limit:

- In a one-off transaction, there might never be reasonable grounds to invoke this Rule.

- In an ongoing relationship, this Rule provides a built-in channel for structured communication.

3.2.2. Video conferencing

How will we do catch-up calls — in person? By phone? By video conference?

- The parties use video conferencing for catch-up calls unless otherwise agreed.

- If A asks for the catch-up call, THEN: A gets to choose the video-conferencing platform, as long as that platform is reasonably available to B.

Note

(). When it comes to choosing a video-conferencing platform — e.g., Zoom, Teams, etc. — presumably the parties will be able to agree on that much, even if their relationship is deteriorating or even becoming hostile.

Pro tip: Parties can conside screen-sharing for "whiteboarding," which reportedly is a key business practice at AI chipmaker Nvidia. See, e.g., Amanda Liang and Willis Ke, Jensen Huang breaks bureaucracy at Nvidia with whiteboard and flat management strategies (Digitimes.com 2024).

3.2.3. Participants

Who's expected to participate in catch-up calls?

- For each catch-up call, each party has appropriate people participate — on any given call, who that would be would depend on the circumstances.

- A is not considered to have breached the Contract just because a particular individual from A did not participate in a catch-up call.

Note

Subdivision 2: There seems to be little purpose for a hard-and-fast rule about who must participate, because that will vary with the parties and the situation — so let's be explicit about that, In the interest of avoiding satellite disputes.

3.2.4. SPUR Agenda

What wil we talk about on a catch-up call?

In any catch-up call, the parties follow any agreed agenda — including (where agreed) the SPUR Agenda:

- Status, both good and bad — things done and left undone;

- Plans — including contingency plans where relevant;

- Uncertainties, such as unknowns; untested assumptions; upsides/downsides; and

- Reports? (by email or otherwise; e.g., to document any agreements reached).

But the parties are free to follow any agenda they want.

Note

(). Structured communications can be helpful and even crucial (see 2.2.3); this section provides a bare-bones framework.

Pro tip: As a reminder: It will often make sense to circulate:

- proposed agenda items; and

- advance copies of relevant documents.

3.2.5. Documentation of agreements

What if something is agreed to in a catch-up call?

A catch-up call does not modify any party's rights or obligations under the Contract except as stated in Protocol 3.1 (amendments) and/or Protocol 3.18 (waivers) when applicable.

Note

This language is intended to make it a breach of the Contract to make such an assertion, with damages for the breach being the opposing party's attorney fees and costs (see 21.18.6).

3.2.6. Meeting minutes; written readouts

Does anyone take meeting minutes? If so, how are the minutes handled?

Meeting minutes for catch-up calls — and/or merely readouts — are encouraged but not required.

Note

(). The term "readout" is used in governmental affairs for one party's brief, unilateral, written summary of a call or meeting — see, e.g., the White House "readout" of a meeting between the presidents of the U.S. and China.

A readout should list:

- significant points discussed, and